The biggest pushback on Serotonin Inhibits Emotions related to Predictive Processing, a major theory in modern neuroscience. It’s an approach that, according to proponents, is a sort of general operating principle for both individual neurons and the whole brain. Unfortunately, most of these proponents write in an obscurantist style1 that leaves the topic a bit mysterious. This essay attempts to briefly describe the theory as simply as possible and argue that it does not conflict with my position.

What is Predictive Processing?

It is a theory in computational neuroscience, meaning that it focuses on the brain as an information processor. It also goes by Predictive Coding when focused on perception and Active Inference when including motor activity. This paradigm inverts the classic view of how the brain works. Instead of stimulus and response - processing sensory input, making a decision, and reacting - the brain is a “prediction machine.” In short, the brain first hallucinates a world, then tries to make reality match its expectations.

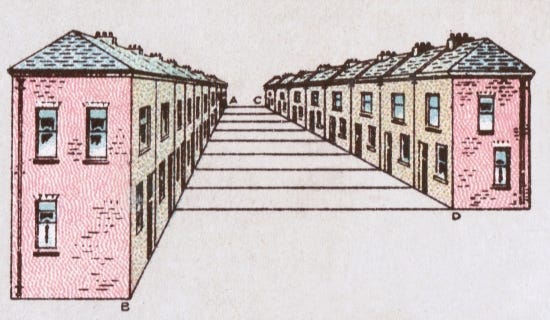

A good illustration is vision. Vision seems like a sort of movie or real-time recording of the world, with the brain more-or-less reconstructing the light patterns that hit your retina, and information flowing bottom-up. But this model has problems. Visual information cannot be mapped 1:1 back to its real-world source; there is always ambiguity. Your brain fills in a lot of detail and missing data. It’s easy to fool your brain, as in visual illusions, by taking advantage of assumptions about perspective and shading. In short, your brain expects certain patterns; these top-down expectations, unconscious inferences, or predictions influence what you see.

The nervous system’s “goal” is to minimize mismatch between expectations and reality. At each level, neurons signal to the level below, and this descending signal is compared to ascending input. When top-down and bottom-up signals match, they cancel out. Only mismatches or “prediction errors” get sent up the chain for further review. Yes, this does sound a lot like a negative feedback control loop.

Prediction errors mean that something newsworthy is happening, something unexpected or unexplained. Perhaps a plane emerging from a cloud as you watch the sky, perhaps a stair step that’s lower than you thought. In each case, the brain must decide whether to care, so error messages come with a precision or confidence level, like an editor asking a beat reporter “How reliable are your sources?”

Now the brain has two ways to respond. First, when the world doesn’t match expectations, the brain can change its expectations to account for the new input. This is perception, more or less. Second, the brain can change the world to match its expectations. This is behavior, more or less. In this framework, bodily movement starts with the brain “predicting” the sensory state of your leg swinging forward, then motor neurons firing to make your leg position match the prediction.2 Yes, it is a weird way of thinking about it.

What does Predictive Processing say about emotions?

These principles apply whether information arrives via your retina, proprioceptive muscle spindles, tongue, or gut. The brain predicts bodily feelings (interoception) the same way it predicts external perceptions.3 There are a couple versions of this.

One says that emotional feelings consist of your brain making sense of bodily changes. If you prefer, “emotional content is generated by active top-down inference of the causes of interoceptive signals.” (Seth 2013) As with vision, your brain constantly compares expected bodily sensations to incoming signals from your body. Mismatches need to be accounted for in some way, and higher-level neurons attribute meaning to ascending prediction errors. Thus, a racing heart and sweaty skin is fear when you’re getting chased by a bear and excitement when you’re about to win a 10k. This is not that different from old ideas about emotion such as James-Lange and Appraisal theory.

The second version says this is too simple. Emotions are not about inferring the causes of bodily changes, they are about “how the brain succeeds or fails to do so over time” (Wilkinson et al 2019). The origin of good feelings is decreasing error, not zero error. For example, your hypothalamus predicts your body temperature is 37C, but it’s actually 35.8. So you feel cold and shiver and pace around and look for a fireplace. Here is the important part: you feel good - positive affect - as you warm up and the error shrinks. Fear arises not from seeing a bear, but from noticing that the bear is gaining on you. The pleasantness or unpleasantness of feelings track the first derivative of prediction error over time.

How does serotonin fit in?

In this framework, the main idea is that serotonin reduces the precision of descending predictions. A confident brain tends to ignore error messages from lower levels, while loosely held “beliefs”4 are revised by new information. By lowering confidence levels, serotonin promotes something like openness, flexible thinking, or plasticity.

The argument rests mostly on the effects of psychedelics like LSD, psilocybin, and MDMA, which activate certain serotonin receptors. In doing so, they cause weird sensory experiences, interpreted as the brain being less reliant on expectations and giving more weight to lower levels of perception. This is why people on LSD see abstract color patterns, unexpected motion, objects changing shape, etc. At higher doses, they “disrupt functioning at a level of the system that encodes the precision of priors, beliefs, or assumptions.” (Carhart-Harris & Friston) This is why psychedelics create a sense of expanding your mind - serotonin activity loosens pre-existing beliefs and constraints.

This could explain the therapeutic effects of serotonergic medications. Psychedelics, especially psilocybin, may help PTSD and depression by dislodging the brain from a web of negative beliefs. The same goes for SSRIs toward OCD, panic disorder, and so on. Many psychiatric conditions are “false inferences” about the body and the world.5 At a very simple level, more serotonin allows the brain to take a beat, reconsider, and let in new information that challenges its expectations.

Does this contradict the view that “serotonin inhibits emotions”?

I don’t think so, but I’m open to counterarguments. Part of the trouble is imprecise (!) terminology, such as the conflation of emotion and feelings. Feelings are the perception of different body states (real or simulated). Emotion is one level up - it includes feelings as well an action tendency and suite of cognitive changes. So it’s incomplete to say that emotions are inference to a body state or change in body state - these other aspects need to be included. Emotional behavior and feelings often co-occur, but not always. In particular, evolution only notices behavior, so the action consequences of an emotion are arguably its most important component.

In this framework, emotions sure seem like high confidence “predictions.”6 Your brain’s model of the world includes, for instance, the hard-wired belief that an unexpected rustling near your feet is a snake. This belief is so confident that your body immediately startles and jumps back, in a reaction almost impossible to prevent. I can only see this as a descending prediction, running the low road from thalamus to amygdala to lateral hypothalamus and on down to proprioceptive and skeletal motor units. Pounding heart and heavy breathing and urge to run soon follow, which are inferred as fear once the rest of your brain catches up. In the same way, breaking up with a partner - even if you wanted it! - engenders sadness and guilt, and thus crying, laying on the couch, and seeking reassurance from friends. These feelings and behaviors stem from a “belief” in your brain that you’re alone, possibly forever. It’s hard to reason yourself out of this, and new information won’t update the belief for quite a while.

So, the idea that serotonin reduces the precision of descending predictions seems to fit just fine with the idea that serotonin (at some receptors) inhibits emotions. 7Modulating signal precision is quite similar to altering its gain, and Predictive Processing often comes across like a reframe of control theory. I am probably missing something. But gobs of research suggest that serotonin broadly opposes the characteristics of emotional responses; it reduces impulsive action, promotes calm, attenuates affect, and opens the mind to alternative evidence. Emotions are ultimately like any other perception and action dynamic, and the same principles should apply. They have high confidence because they are heuristics; their purpose is mostly to prompt quick action, and specifically not to allow time for questioning and weighing multiple evidence streams. Much of the time, irrationality is the point.

Seth and Friston, 2016: “with a good generative model, these movements will also fulfil visual and other exteroceptive (e.g. somatosensory) predictions. This follows because descending (multimodal) predictions emanate from a deep generative model that effectively assimilates prediction errors from all modalities—including interoception. In this context, an important and sometimes overlooked aspect of active inference is that it implies a counterfactual or conditional aspect. That is, in order for an action successfully to reduce prediction error, the brain must represent not only the hidden causes of current sensory signals but also must use these representations to predict how sensory signals would change under specific actions [35]. Interestingly, it has been suggested that such counterfactual aspects of perceptual prediction may underlie basic properties of perceptual experience, such as ‘presence’ or ‘objecthood’."

Ibid: “In brief, perception can be understood as resolving (exteroceptive) prediction errors by selecting predictions that best explain sensations, while behaviour suppresses (proprioceptive) prediction error by changing (proprioceptive) sensations.”

Ibid: “Replacing proprioceptive signals with interoceptive signals, one can see how autonomic reflexes can transcribe descending interoceptive predictions into physiological homoeostasis (e.g. blood pressure, glycaemia, etc.). Importantly, interoceptive predictions constitute just one stream of multimodal predictions that are generated by expectations about the embodied self. On this view, interoceptive signals do not cause emotional awareness, or vice versa. Instead, there is a circular causality, where neuronally encoded predictions about bodily states engage autonomic reflexes through active inference (see below), while interoceptive signals inform and update these predictions.”

Ibid: “‘Explanations’, ‘hypotheses’ and ‘beliefs’ should in this context be understood not as consciously held mental states, but as neuronally encoded probability distributions (i.e. Bayesian beliefs) over the hidden causes of sensory signals. The biophysical encoding of these ‘beliefs’ is, technically, in terms of sufficient statistics like the mean or expectation of a distribution.”

Ibid: “Very generally, the (predictive coding) process theory that we have sketched above for active inference speaks to the synaptic mechanisms that might underlie false inference in psychiatric conditions: in brief, the formal constraints implicit in predictive coding require a modulatory gain control on ascending prediction errors.”

Ibid: “Interoceptive predictions can perform physiological homoeostasis by enlisting autonomic reflexes. More specifically, descending predictions provide a homoeostatic set-point against which primary (interoceptive) afferents can be compared. The resulting prediction error then drives sympathetic or parasympathetic effector systems to ensure homoeostasis or allostasis, for example, sympathetic smooth-muscle vasodilatation as a reflexive response to the predicted interoceptive consequences of ‘blushing with embarrassment’.”

So why do people like taking psychedelics? My response is: do they? These drugs have never been that popular, and a lot of people find them unpleasant. But OK, some people clearly enjoy the experience. I have two thoughts here. First, people do enjoy having their expectations lightly violated. This is the basis for humor and art and thrill-seeking. The cycle of uncertainty and resolution is rewarding - it’s negative reinforcement. So LSD creates a lot of uncertainty, which hopefully gets resolved in a positive way. Or maybe not, as in a bad trip. Then there is MDMA, which more directly generates positive affect. It seems relevant to point out that MDMA is an amphetamine derivative which increases dopamine and norepinephrine in addition to serotonin.

Excellent explanation of Predictive Processing!

It’s so good I’m going to have a hard time explaining it differently in my upcoming post! Thanks

Timely! I am presenting a similar topic at a conference this weekend (afterwards I plan to share my abstract here on substack). What I find most interesting is the idea of manipulating one's 'network of priors' or 'web of beliefs' as a means to introduce new information instead of the status quo of 'persuading' or 'convincing' the mind's preexisting framework. That unique (and scary), and brings with it a host of new ethical quesitons