Rates of psychiatric illness and treatment have surged in recent decades, sparking talk of mental health crises in adolescents, 20-somethings, parents, and everybody else. There is something to this:

One account of these changes starts around 2012. It’s a public health story, with smartphones and social media in the role of toxic exposure1 and adolescents as the susceptible group. It’s a good story! I love it as much as I hate my iPhone. But its model is flawed, only allowing for one-way push from stressor to distress to diagnosis to treatment. It misses the give-and-take at each step, and the medical premise is incomplete.

Whether or not there is greater need in the medical sense, people are definitely “consuming” more mental health care - psychiatric medications, counseling, and diagnoses - in an economic sense. There are many causes of rising consumption, from greater supply to price regulation to marketing-driven demand to low-cost substitutes. Each of these has occurred in recent years. In short, people now use more mental health care because it got cheaper, more desirable, and easier to obtain.

Mental health care exists in a market

Buyers are patients and sellers2 are psychiatrists, psychologists, primary care physicians, social workers, drug manufacturers, and more. The products are pharmaceuticals, psychotherapy, and a diagnostic label. This last good can be very useful, and you’d be surprised how often it’s all that patients want.

When the market3 expands, established patients get more treatment and new patients dip their toes in. The marginal care tends to have, well, marginal value. This manifests as self-diagnosis, previously obscure diagnoses coming into fashion, lower thresholds for treatment, the slippage of any emotional distress into pathology. As with pornography, the demand for mental health care is far more elastic than expected.

But people can’t pick up SSRIs from a mall kiosk; don’t doctors gate-keep all this? Well, less than you’d think. For one thing, we now ask more about depression and anxiety and identify more cases. The US Preventive Services Task Force first recommended blanket screening for depression in all adults in 2009, which is interesting timing. For another, all incentives push toward making a diagnosis. Physicians and patients both want to put a name on things, and there seems little harm in labeling mild depression or anxiety. It validates suffering, while withholding a diagnosis risks dismissing it, so we err toward false positives. More practically, each prescription and referral must be linked to a problem in the electronic record.

Diagnosis is a collaboration, especially in mental health. We ask certain questions, and not others, and patients bring up certain topics, and not others. If a patient agrees to being sad, not sleeping, and feeling guilty all the time, what then? And if they disclose that they were abused as a child and think about it often, have a hair-trigger temper, and avoid their family, should we not recommend counseling? Physicians, even psychiatrists, have no special powers here.

These dynamics aren’t new, though, so what changed?

Psychiatric drugs got cheaper

Since 2000, pharmaceuticals for common psychiatric conditions aged out of patent protection. After generic entry, supply increases as more sellers enter the market, leading to lower prices - about 80-85% less! Cheaper prescriptions and more treatment are the stated goal of policies to improve affordability.

Generics expand the market to “include price sensitive consumers who formerly were either consuming a drug in a different molecule class, a different form, or doing without drug therapy.” In other words, as the price goes down (hooray!) the quantity of drugs sold goes up (hooray?).

Drug prices definitely fell during this period. For the SSRI sertraline, consumer cost per month dropped from ~35 dollars in the mid-2000s to ~6 dollars by the mid 2010s. Total Medicaid spending on antidepressants peaked in 2004 ($2 billion) then declined through 2018 ($750 million). Authors of that paper note that “generic drug prices steadily decreased over time” while utilization increased. From 2013 to 2018, both out-of-pocket costs and total expenditures per prescription fill went down for antidepressants and antipsychotics. For antipsychotics, generic drug claims grew 35% from 2016 to 2021.

According to the DEA, total dispensing of stimulants jumped 58% from 2012 to 2022; note how this follows the generic entry of long-acting Ritalin (methylphenidate) and Adderall (amphetamine) products. More recently, stimulant prices shot up amid shortages.

Total out of pocket costs went down

At the same time, new regulations made all mental health treatment more affordable. In 2008, Congress passed the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, which required large health plans to cover psychotherapy the same as, say, physical therapy. In 2010, the Affordable Care Act closed remaining loopholes and mandated broader coverage. Limits on copays and coinsurance are price ceilings. There are good reasons to regulate medical prices, and everybody should have medical care, but the tradeoff is excess demand.

The new laws achieved their goal as point of service costs dropped. By the mid 2010s, people with psychiatric conditions were better able to afford mental health care. Young adults, now on their parents insurance, saw declining out of pocket costs for behavioral health in particular. For people aged 18-25, “mental health treatment increased by 5.3 percentage points relative to a comparison group of similar people ages 26–35.” Even for employer plans, in-network prices and cost-sharing decreased from 2007 to 2017:

In addition, the ACA expanded Medicaid in states that wanted it. Total enrollment grew from 54 million in 2010 to about 90 million in 2023. The express purpose of Medicaid is to enable affordable medical treatment, including mental health care, for low-income individuals. About 40% of enrollees have a psychiatric or substance use diagnosis, and most states do not have copay requirements.

Stigma reduction is marketing

Negative attitudes about mental illness and its treatment act as a sort of tax, an additional cost to the consumer that prevents some people from seeking care. Stigma is a reputational harm, separate from whatever value the diagnosis or treatment holds, and it’s borne mostly by patients. Reducing the “stigma tax” lowers prices so consumers are more willing to seek treatment. Recognizing this, in 2000 both the US Surgeon General and the World Health Organization declared stigma one of the greatest obstacles to better mental health care.

In subsequent years, anti-stigma and mental health awareness programs popped up all over. By the 2010s, there were state-led campaigns in Michigan, Texas, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Ohio, North Carolina, and more. New York has offered residents a tax break for donations to its anti-stigma fund since 2016. In 2015, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) started a new social media marketing campaign, getting private firms like Boeing, Bank of America, and Google to sign on to their StigmaFree pledge. Other companies joined efforts like the Mental Health Coalition, a group of “the most passionate and influential organizations, brands, and individuals who have joined forces to end the stigma surrounding mental health.” There is evidence that such programs lead to greater help-seeking in target populations.

For another example, in 2011 the California Mental Health Services Authority implemented a wide array of stigma reduction efforts. Activities began in elementary schools with an “interactive knowledge-based game” about mental health promoted on the radio and internet, social media marketing and celebrity PSAs targeting 14 - 24-year-olds, and a documentary for older people. Seriously, check out this PDF; it’s got a deliverables timeline and everything. The RAND corporation evaluated CalMHSA’s efforts, drily concluding the “California campaign appears to have increased service use by leading more individuals to interpret symptoms of distress as indicating a need for treatment.”

The line between “anti-stigma campaign” and “straight-up marketing” gets blurry fast. For instance, celebrity-singer Adam Levine partnered with Shire pharmaceuticals to promote ADHD awareness with the Own It campaign, which kicked off in 2012. ADHD awareness month correlates to increased Google searches for ADHD treatment and medication. The Stamp Out Stigma campaign is run by what appears to be a trade group of insurers and pharmacy benefit managers.

Views of mental illness certainly evolved over the past twenty years; I think this is self-evident. Awareness became a grassroots phenomenon, interspersed with healthy patches of astroturf. Reddit has hundreds of forums focused on mental disorders. Users compare medication responses, discuss their various diagnoses, and coin new ones like AuDHD. TikTok is a vector for spreading functional neurological disorders. ADHD influencers are all over Instagram. Notably, neither those individuals nor industry groups are required to disclose their financial ties, since the marketing is classified as disease awareness rather than drug advertising.

Convenience is King

With COVID, the switch to telehealth visits was a huge reduction in hassle. Including travel time, an hour-long in-person visit is twice that, and even more for rural and non-driving patients. For office workers now, remote sessions slot into the Outlook calendar between other meetings. For blue collar workers, visits fit in a lunch break; I’ve seen dozens of patients in a break room or sitting in their car outside the warehouse. There are ancillary savings, too. For parents, remote visits mean saving $100 per month for childcare; I’ve seen patients while toddlers were napping and kids were watching Bluey. This time cost was, again, borne almost entirely by the patient, and its elimination was a steep price drop that accelerated use of mental health services in the last four years.

Counter Arguments

Mental health is worsening all over, not just in the US.

Many of these factors are present elsewhere. The affordability of modern antidepressants should take a similar brand-name to generic trajectory, even in national health systems like Canada or the UK. England codified “parity of esteem” for mental and physical health in 2012, about the same time as ACA implementation in America. Stigma reduction is also international. In England, Time to Change was an online and mass-media marketing campaign launched in 2007, emphasizing that mental illness is common and that discrimination is “worse than the illness itself.” Program evaluation found that the campaign succeeded in increasing intended help-seeking. This article references “an intensification of anti-stigma campaigns across Europe” since the 1990s, though without specifics. Beyond Blue in Australia and Opening Minds in Canada are similar. Telehealth visits became a thing everywhere in 2020-2021.

I am very curious about readers' impressions from their own countries.

Doesn’t the rise in diagnosis and treatment reflect actual change in emotional distress and symptoms?

It’s not clear that the underlying need has changed. I’m skeptical of effects seen only in certain subgroups, so let’s look at all adults. Americans have a surprisingly consistent view of how their life is going:

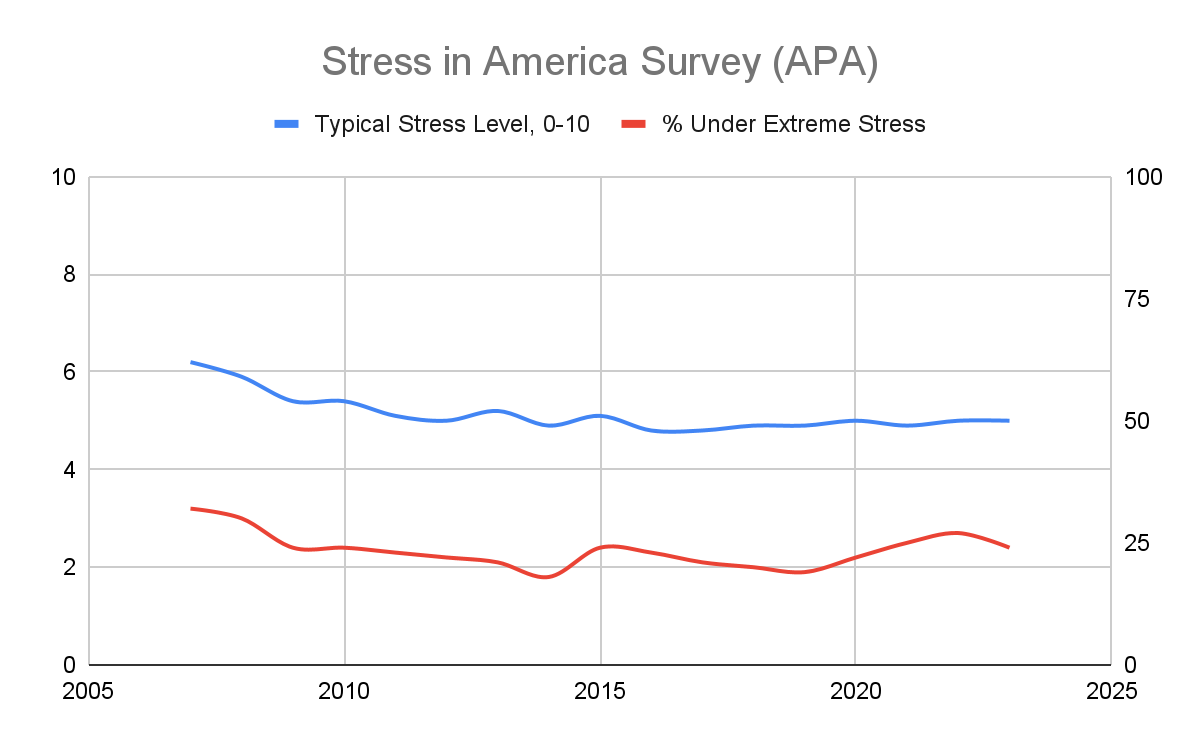

And self-reported stress has, if anything, declined slightly since the mid-aughts:

In a public health framework, there is a tension between rising rates of mental illness and treatment on the one hand, and basically stable life satisfaction on the other. In economics, this is consistent with movement along the demand curve.

What about suicide rates?

The real question is why suicide rates were so low in the 90s and 2000s. Increased suicidality in adolescents is the major argument by Jon Haidt et al for the seriousness of the situation. I dislike phones and social media, so I am sympathetic. But using the 2000s as a baseline is misleading since we can justifiably call that era an anomaly. In addition, as I’ve written, suicide has many antecedents, and it’s just tough to reason backward from a rate change. The base-rate is low, confounds are everywhere, and sub-group analysis is tricky.

Here is counter-intuitive data for the whole US back to 1900:

That’s wild. It’s hard to imagine they were overcounting suicide in the 1910s and 1930s. Medical care improved mid-century, but still. Note the steady drop from 1985 to 2000, then steady rise back.

Separating out young people, here is data from 1970 to present:

It’s a bit arbitrary to imply that 10 deaths per 100k is the natural rate, and anything above that demands explanation. We can just as easily say that suicide mortality has reverted to historical levels.

Conclusion

Psychiatry’s subjectivity makes it especially sensitive to price, social mores, convenience, and fads. A counterfactual might help here. I don’t think that rates of psychiatric diagnoses and mental health treatment would be this high if SSRIs were $50 per month, therapy was $250 out of pocket, and no one accepted social anxiety as a valid reason to miss class. Emotional distress, always with us, would find other manifestations and labels.

If we grant psychiatric diagnoses the status of medical illness, they must remain a harm, a loss to be avoided and indemnified, not a good to be sought out. Diagnoses are useful - they enable treatment and put a name to the person’s experience. They might also provide an answer to questions like: Why do I feel bad? Why do I make poor decisions? Why am I not more successful? But when diagnoses become a facile excuse, or when they bring accommodations and status, the system breaks down.

Trade-offs are unavoidable; making mental health care more affordable, more accessible, and more familiar means that more people partake. It will be helpful to many, neutral for some, and harmful to others. But soon enough, people will tire of depression and PTSD and ADHD as the source of their problems. We’ll move on to a different understanding of troublesome behavior and thoughts and feelings, because all this has happened before, and will happen again.

There’s room for COVID, climate anxiety, economic inequality, loss of community, political polarization, and more

There are about 45,000 psychiatrists active in the US, a number gradually declining due to retirements but offset by growth in non-MD prescribers. The number of psychologists per capita has increased some since 2014, but the overall distribution remains highly skewed toward urban areas; about half of US counties have zero psychiatrists or psychologists.

In contrast to neurology or oncology, mental health has distinct tiers that don’t mix much. The “down-market” comprises public services and not-for-profit agencies serving low income individuals. Consumers have low to zero out-of-pocket costs. The middle tier is patients with private insurance and contracted providers. About three-fourths of therapists accept insurance, and patients mostly stay in-network. Copays run $35-45, which is a large subsidy since private pay rates are more like $125-175 per session. At the high-end, boutique practices of psychiatrists and psychologists oriented to long-term psychotherapy charge fees several times the mean.

Excellent and novel perspective.

As to the points made:

Cultural change, and yes, economic and adjacent change, more likely than actual significant increase in severe distress. That said, a cultural change that leads to reframing experiencing X as disorder/disease effectively and very realistically CREATES additional distress, so there's that.

On the young people, I also suspend judgement but I suspect defences, workarounds and adjustments to digital native existence will evolve, and the negative effects (if meaningful now) will abate.

Looking at the age-adjusted suicide plot, maybe this is just coincidence but its kind of striking to me how much drops in the suicide rate seem to line up with US wars.

1916-18 and 1942-45, WW1 and WW2 respectively, are clear low points in the chart. The start of the Korean war in 1950 also corresponds to a stark drop. The Vietnam war is less obvious but 1964-1970, when US involvement really ramped up also corresponds with less suicides, with the year of the Tet offensive 1968 being a local minima.

The early aberrantly low early 2000's also corresponds to the war on terror, although this one is a pretty bad match because suicides reached a minimum before 2001. Also the dip around 1976 doesn't match up to the start of a war.

There's a lot of plausible reasons why war might lower the count of suicides. Maybe the services of young people in the military reduces their chance of suicide, maybe a wartime economy where labor is in high demand reduces economic stress that may cause suicide, maybe suicides are undercounted in wartime for some administrative reason, maybe war spurs a greater sense of patriotism and belonging to the nation which reduces suicide. Or maybe its just a coincidence.

Also A+ ending to the article!