A CDC report this year earned extensive media coverage with data on the poor mental health of U.S. high school students. In addition to sky-high rates of sadness and hopelessness, 30% of girls endorse seriously considering suicide, up from 19% in 2011, with 13% reporting a suicide attempt in the past year. Subsequent commentary has focused on potential causes for the increase in negative feelings, whether social media, smart phones, academic pressure, climate anxiety, or politics. As someone who works in mental health, all of this discussion certainly jibes with my daily experience.

Strangely, the part about escalating suicidality in adolescents seems underemphasized in this discourse. I think it’s because of an underlying assumption that severe emotional distress, often labelled as depression, leads naturally to suicidal thoughts. It’s expected that there’s a sort of monotonic relationship between negative feelings and suicide risk, which culminates in suicidal behavior.

But this model has many shortcomings. For one thing, why do some people with severe depression attempt suicide, and others never do? What about people with no apparent history of emotional problems? There are dozens of other risk factors including impulsivity, physical health problems, a family history, suicide clusters, and access to firearms.

For that matter, being “suicidal” encompasses a lot. Is vague ambivalence about death really on a spectrum with carefully planned and rehearsed attempts? What about people who impulsively swallow pills during an argument with their partner? What framework accounts for elevated suicide risk in groups as disparate as LGBTQ youth, old white men, heroin users, and traumatized veterans?

In short, good theories of suicide are hard to come by. Past attempts to explain it have focused on too little (or too much!) integration of individuals with society, acute psychic pain due to thwarted needs, or hopelessness. The best-known modern approach is Thomas Joiner’s Interpersonal Theory of Suicide, and Why People Die By Suicide (2005) is his book length treatment. Joiner offers a global critique of most academic and folk theories:

Many explanations for suicide fail fairly obviously in the face of [low] prevalence rates. If suicide is due to factor X, it must be explained why this factor is fairly common and suicide less so. For example, mental illness is commonly invoked as an explanation for suicide…But mental illness alone does not provide a satisfying explanation for suicide, because mental illness is much more common than suicide. How should we explain all those people with mental illness who do not die by suicide? Moreover, the absence of our hypothetical X factor in some suicides needs to be explained.

According to Joiner, the best explanation for this (and all the other data) is that a serious suicide attempt requires three distinct conditions, each necessary but not sufficient.

Desire for Death

People usually try their best to stay alive. Why would a "desire for death'' emerge in an organism so shaped by evolution? Joiner argues that two social factors are key.

No more fiendish punishment could be devised, were such a thing physically possible, than that one should be turned loose in society and remain absolutely unnoticed by all members thereof. If no one turned around when we entered, answered when we spoke, or minded what we did, but if every person we must 'cut us dead,' and acted as if we were non-existent things, a kind of rage and impotent despair would before long well up in us, from which the cruelest bodily torture would be a relief.

William James (1890) via Joiner

The first is Thwarted Belongingness. Put simply, humans need frequent positive interactions with others. Personal connections create meaning in life and act as a buttress - it's common for even severely depressed people, when asked about suicide, to say something like "I could never do that to so-and-so."

Unsurprisingly, there’s a lot of evidence for the role of social isolation. Living alone, loss of a partner, and divorce all increase risk, while pregnancy and having children are protective. Major Depressive Disorder creates at least a feeling of disconnection, while substance use often leads to actual estrangement from family and friends.

The second component is Perceived Burdensomeness. Suicidal people view themselves as incompetent, so much so that it brings down the people around them. They face a choice between "escalating feelings of shame, on the one hand, or death on the other hand." Eventually they rationalize death as leaving their family better off. For example, Kurt Cobain's suicide note mentioned that his daughter “will be so much happier without me." Joiner also points to premodern societies that sanction a form of suicide when elderly or infirm members lose the ability to contribute.

Research also supports a correlation here. One study concluded that "genuine suicide attempts were often characterized by a desire to make others better off, whereas non-suicidal self-injury was often characterized by desires to express anger or punish oneself." Another looked at chronically ill patients who needed caregiving from their spouse. One might expect spousal support to reduce suicidality, but instead the correlation was positive - interpreted as patients’ sense of burden on their spouse.

The Ability to Enact Lethal Self-Injury is Acquired

Joiner asks:

If emotional pain, hopelessness, emotional dysregulation, or any variable is crucial in suicide, how then to explain the fact that most people with any one of these variables do not die by or even attempt suicide? How do we make sense of the anecdotal and clinical evidence suggesting that there are people who genuinely desire suicide but do not feel able to carry through with it?

His answer is that individuals acquire the ability to harm themself, overcoming fear of pain and death, via particular life experiences.

One route is practice, or “working up to it.” A history of multiple attempts predicts future death by suicide, while research, planning and rehearsal are forms of practice as well. Consistent with a trajectory of escalation, the number of previous suicide attempts predicts the severity of medical damage in later attempts.

Other forms of bodily harm accomplish the same end: cutting, IV drug use, tattoos, combat exposure, childhood physical abuse, and even aggression toward others. Repeated exposure to any painful or provocative stimuli leads to habituation and lessening of aversive effects. Just as a veteran skydiver replaces fear with exhilaration, self-injury can become reinforcing.

This is a plausible framework for why certain types of people are at such high risk. For instance, the ratio of attempted to completed attempts in young people is very high (100:1 according to Joiner) but decreases dramatically in the elderly. This fits a model in which people acquire the capacity for more serious self-harm over time. Substance use is such a risk because it entails repeated provocative experiences (IV drug use, alcohol related injuries) as well as the isolation and burdensomeness of late-stage addiction.

Problems

At times Joiner really strains the model, while ignoring some major topics altogether.

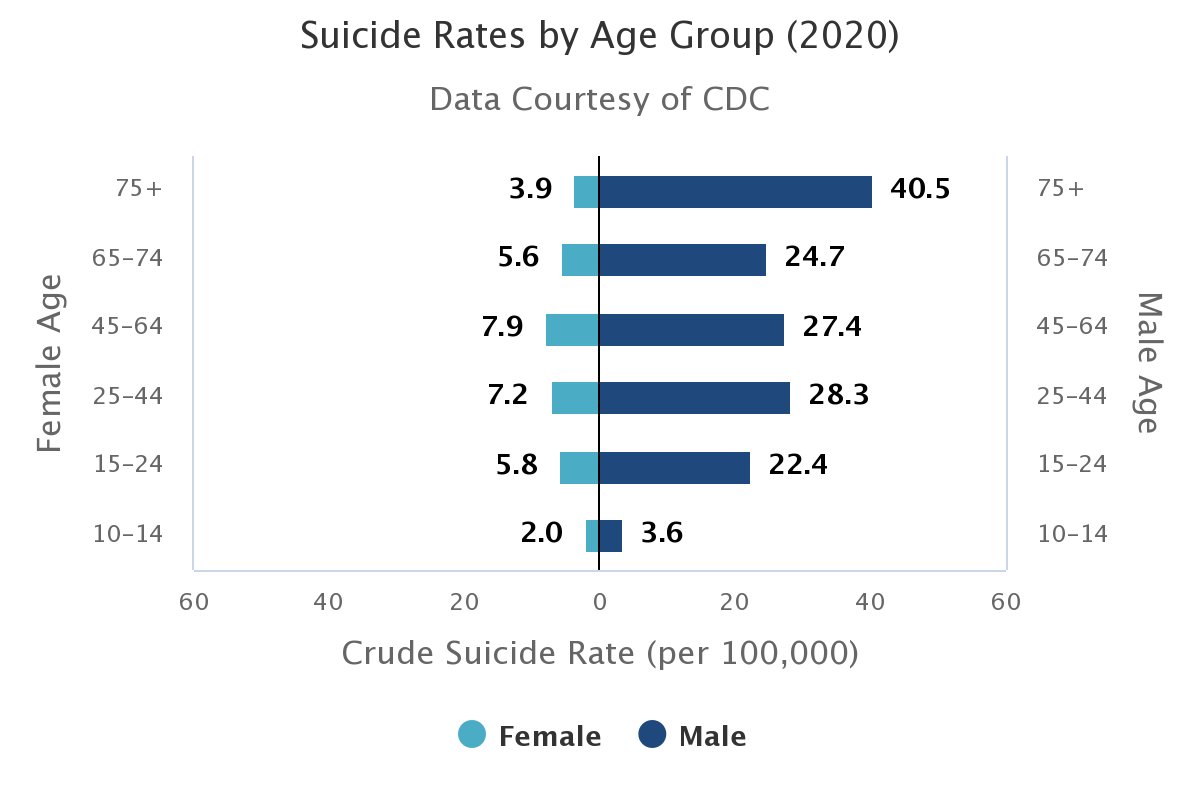

Above all, his take on firearms is perplexing. Access to guns is an undeniable risk factor. Their use probably explains why men die more often despite women’s higher attempt rates. Joiner only comments that “having guns around acquaints people - renders them fearless - about a potentially lethal stimulus.” Elsewhere he mentions that greater feelings of burdensomeness correlate to more lethal means, such as firearm vs overdose. All told, he spends only a couple pages on the topic, and attributes their role to “vicarious habituation.” This seems inadequate!

Why People Die By Suicide also discounts a role for religious beliefs or stigma. The single mention of religion arrives during discussion of black Americans’ relatively low suicide rates, in which Joiner almost grudgingly admits that “contact with religious institutions and perhaps support from others is consistent with the assertion that the need to belong, when satisfied, can buffer from suicidality.” Even an atheist like me can admit that religious prohibitions against suicide are likely protective, a view that’s generally accepted in clinical contexts.

Relatedly, you might wonder about culturally approved forms of suicide: terrorists, martyrs, kamikaze pilots, and the historical Hindu practice of Sati. Joiner tries to accommodate these by debating semantics (“classifying [9/11 terrorist] deaths as suicides seems quite arguable”) and a good deal of hand-waving (“the pilots’ need to belong has been met by death”).

Finally, Joiner rejects the possibility of impulsive suicide attempts, asserting without further explanation “I am very skeptical of this concept, and I doubt that true ‘spur of the moment’ suicides exist.” He does acknowledge a role for impulsive personality traits, touching on literature that links low CSF serotonin metabolites, impulsive/aggressive behavior, and greater suicide risk. However, he maintains that “impulsivity only relates to suicidal behavior because impulsivity facilities exposure to provocative and painful experiences.” This may be true, but I can’t see a good reason to wholly deny the occurrence of spur of the moment suicides.

Altogether, these are substantial flaws. The theory also doesn’t account well for established risk factors like chronic pain, insomnia, anxiety, psychosis, and feeling trapped.

Energy States and Suicide

Joiner’s most convincing move is separating a desire for death from the capability to self-harm. Starting from this insight, I can’t help but see a different sort of model.

Being alive and being dead are two different states. Being alive is usually preferred.

Sometimes the states seem equivalent, for instance if prolonged disconnection makes life feel pointless.

More rarely, death actually seems preferable. This often involves a belief that others are better off without them, but can also occur anytime quality of life is low enough.

Even in such cases, killing oneself is hard! This state change involves a substantial barrier, or activation energy. The very act of attempting is a high-energy transition state. The higher the barrier, the less likely a suicidal person is to actually make an attempt.

Factors that raise the activation energy include fear of pain, fear of death, and prohibitions against suicide. Factors that lower the barrier include practice, impulsivity, and any beliefs that make suicide more acceptable, such as specific cultural beliefs or exposure to suicide attempts by others.

The “favorability” of the change depends on the relative desirability of life and death. Desire for death isn’t always due to interpersonal problems - there are other factors like chronic pain, severe insomnia, and psychosis.

The “rate” is determined by the height of the barrier, or activation energy. People with high barriers are unlikely to ever attempt suicide, while those with a low barrier could act any time the desire is present. Viewing this as a barrier to overcome, rather than an acquired capacity, seems to better account for innate fear of pain and death, as well as cultural prohibitions that effectively raise the threshold for suicide. Conversely, firearms and alcohol act as catalysts, lowering activation energy by their presence. Finally, more impulsive people, kinda by definition, have lower barriers to action across the board.

Implications

Let’s go back to Joiner’s model, which suggests a grim future. Suicidal thoughts are already prevalent among young people, whatever your preferred sociological explanation. As these cohorts age, they will only gain more experience with various forms of self-harm, increasing the capacity for serious suicide attempts. The opioid epidemic, declining marriage and fertility rates, remote work; these trends all push in the same worrying direction.

On the other hand, facile stories about suicide are misguided. At the societal level, dozens of factors interact in contingent ways. For instance, we might see opposing trends like increasing social isolation but decreasing substance use. In the right circumstances, it’s perfectly consistent for high levels of suicidal ideation to coexist with low suicide rates. Finally, blanket attributions of suicide to diagnosable mental illness miss the role of family, employment, religion, physical health, trait impulsivity, firearm access, and more.

But, let’s imagine that we took suicide seriously. Historical and international comparisons suggest it’s tractable. Consistent with the model, here are a few policies that might help.

If interpersonal disconnection is a main driver, smartphones and social media sure seem like accelerants. Legislation could raise the minimum age for participation. As in the anti-smoking crusade, there could be marketing campaigns against social media and soft coercion such as restaurants with no smartphone zones. Compulsive phone use should be unseemly and low-status. Remote work also seems bad for belongingness, for that matter. More broadly, policies to increase employment, marriage and fertility rates should help here.

The elderly are especially prone to feeling burdensome. In the U.S., I could see a benefit from adding long-term care insurance to Medicare (Part E?) and expanding caregiver tax credits.

About a quarter of suicide deaths involve alcohol, and reducing alcohol consumption through taxes or other restrictions is straightforward. IV drug use is another huge risk; methadone and buprenorphine treatment could be deregulated.

Joiner notwithstanding, impulsive suicide definitely occurs. Overdose deaths can be reduced by regulating risky medications such as opioids, sedatives, aspirin, acetaminophen, and antidepressants. Easy changes include decreasing pills per package, mandating blister packs instead of bottles, and limiting dose per pill. When overdosing is harder, it happens less.

If you accept my framing of firearms as a catalyst for suicide, then reducing their availability should have outsize impact. This is obviously contentious, but even in the U.S. various laws prohibit gun ownership by people who have been involuntarily committed, not to mention convicted felons and repeat DUI offenders. The scope of such laws could be expanded, for instance by lowering the threshold from multiple DUIs to one.

As a closing speculation, I’d like to raise the idea of unintended consequences from modern attitudes about suicide. Traditionally it has been viewed as an immoral, or at least weak and selfish act, sharply condemned by most major religions. Such prohibitions would be expected to raise the barrier to suicide; the point of stigma, after all, is to affect behavior. But this cuts both ways. In recent decades, suicide is progressively medicalized, linked ever tighter to mental illness, and often described in passive terms (“so-and-so lost their battle with depression;” “died by suicide” rather than committed suicide). In short, the act of suicide is being destigmatized, and in particular being viewed as a disease outcome rather than a sin. This impulse is understandable, and I want to reiterate that I’m as secular as it gets. But if you believe that incentives matter, and that choice happens at the margin, this shift in thinking should concern you. The more that suicide is seen as understandable, perhaps even blameless, the more common it will be. What else would we expect?

I’m as surprised as you are that the author doesn’t believe in impulsive suicide. For me this explains why restricting access to lethal means reduced suicide rates https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC478945/pdf/brjprevsmed00022-0018.pdf

I’m also skeptical that suicide risk in the elderly is related to repeated suicide attempts over a lifetime. Anecdotally, when I have seen serious suicidal acts in elderly people, these have occurred ‘de novo’ in people without much psychiatric history.

Thank you, I’m glad I found your substack.